Rastafari, occasionally called Rastafarianism, is an Abrahamic religion that developed in Jamaica during the 1930s and has since expanded into a global cultural and spiritual phenomenon. While it originated in the Caribbean, its expansion throughout Africa is an important aspect of its story. The piece examines Rastafari’s origins, key principles, and spread to Africa. It also looks at how various African countries have adopted and modified the movement.

Origins of the Rastafari Movement

The Rastafari movement began in Jamaica during the 1930s, influenced by religious, social, and political factors. A key event was the coronation of Ras Tafari Makonnen as Emperor Haile Selassie I of Ethiopia in 1930. Many Jamaicans, especially those of African descent, saw Haile Selassie as a divine figure who would free them from oppression. This belief was largely influenced by Marcus Garvey, a black nationalist who promoted African pride and the return to Africa.

Rastafari’s beliefs are rooted in the Bible but differ in interpretation. Followers believe Haile Selassie is the living God (Jah) and that Ethiopia is the Promised Land. The movement emphasizes African identity, resistance to oppression, and living naturally. Common practices include wearing dreadlocks, using cannabis in ceremonies, and following a specific diet (ital).

Early Spread of Rastafari Ideology

The Rastafari ideology began to spread beyond Jamaica through the Jamaican diaspora. As Jamaicans moved to other parts of the Caribbean, North America, and the UK, they took their beliefs with them. Reggae music, especially Bob Marley’s songs, also helped spread Rastafari ideas globally.

However, for Rastafari to take root in Africa, a deeper connection was needed. The movement’s Pan-Africanist ideology, viewing Africa as a spiritual homeland, played a crucial role. This set the stage for its acceptance and growth in Africa.

The Influence of Haile Selassie and Ethiopia

Haile Selassie I was central to the Rastafari movement. His image and legacy are key to its theology. In 1966, Haile Selassie visited Jamaica, significantly impacting the Rastafari community. This visit legitimized their beliefs and strengthened their connection to Ethiopia.

Ethiopia, having resisted colonization, symbolized African pride and resilience for Rastafarians. Haile Selassie granted land in Shashamane to people of African descent willing to return. This settlement became a symbol for Rastafarians seeking to reconnect with Africa.

The Spread of Rastafari in Africa

The spread of Rastafari in Africa was influenced by several factors:

1. Pan-Africanist Ideology

Rastafari’s Pan-Africanist message resonated with many Africans, especially after gaining independence from colonial rule. The movement’s focus on African pride, resistance to oppression, and spiritual connection to Africa found a ready audience among those redefining their identity.

2. Reggae Music

Reggae music, especially by Bob Marley, played a significant role in spreading Rastafarian beliefs across Africa. Songs about social justice and liberation connected deeply with African listeners. The popularity of reggae music helped spread Rastafari ideology and fostered a sense of unity.

3. Migration and Diaspora Connections

Rastafarians migrating to Africa, particularly to Ethiopia, Ghana, and South Africa, helped spread their beliefs. These migrants formed communities and engaged with locals, embedding Rastafari within African societies. The Shashamane settlement in Ethiopia became a crucial link between Rastafarians and their spiritual homeland.

Rastafari in Specific African Contexts

The reception and adaptation of Rastafari varied across different African countries, influenced by local culture and politics. Here’s a look at its development in Ethiopia, Ghana, and South Africa.

1. Ethiopia

Ethiopia is central to Rastafarian beliefs. It is considered the Promised Land, and Haile Selassie is seen as the living God. The Shashamane settlement, on land given by Haile Selassie, became a hub for Rastafarians reconnecting with Africa. Despite challenges like economic hardships and cultural differences, Shashamane remains a symbol of the Pan-Africanist vision.

2. Ghana

Ghana is another key hub for Rastafarians in Africa. Its rich culture, history of Pan-Africanism, and openness to the African diaspora make it attractive to Rastafarians. In Ghana, the Rastafarian community promotes cultural exchange and education, blending Rastafarian and traditional African beliefs.

3. South Africa

In South Africa, Rastafarians have been active in social justice movements, challenging oppression and promoting unity. The movement’s emphasis on African identity and resistance to oppression resonates with many South Africans, especially in marginalized communities. Reggae music has also become a significant part of South African culture.

Challenges and Future Prospects

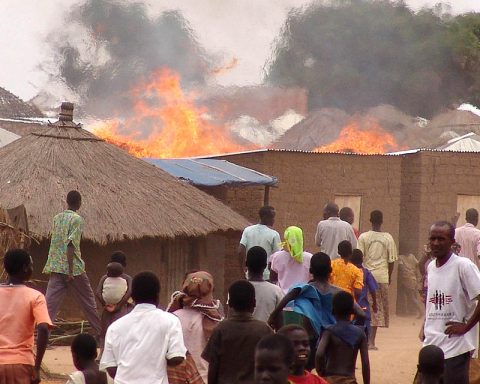

Despite its growth, the Rastafari movement in Africa faces challenges like economic difficulties, cultural differences, and political instability. Additionally, its unconventional beliefs can sometimes lead to misunderstandings.

However, the future looks promising. The movement’s focus on African identity, social justice, and spiritual consciousness continues to inspire many Africans. The ongoing popularity of reggae music and the recognition of Rastafarian cultural contributions support its influence.

As African countries continue to navigate post-colonial identity and development, Rastafari offers a unique perspective that combines spiritual, cultural, and political elements. Its commitment to Pan-Africanism and African pride provides a powerful framework for addressing contemporary challenges.

Conclusion

The growth and spread of the Rastafari movement in Africa are significant parts of its history. From its beginnings in Jamaica, influenced by Marcus Garvey and Haile Selassie, Rastafari has grown into a global movement. In Africa, it has found fertile ground, resonating with post-colonial struggles and aspirations.

The movement’s Pan-Africanist ideology, the power of reggae music, and the migration of Rastafarians to Africa have all contributed to its growth. While challenges remain, Rastafari continues to offer a compelling vision of African identity and resistance to oppression.

As the movement evolves, its principles of African pride, social justice, and spiritual consciousness will likely continue to inspire people across Africa and beyond. The journey of Rastafari from Jamaica to Africa underscores the enduring relevance and transformative potential of its message for a more just and spiritually fulfilling world.

Biblical Citations

Genesis 1:29

Leviticus 11:41–42

Numbers 6:5–6

Psalms 18:8

Psalms 68:31

Daniel 2:31–32

Daniel 7:3

Luke 14:11

Revelation 5:2–3

Revelation 19:11–19

Revelation 19:16

Revelation 22:2

References

- Barrett, Leonard E. (1997) [1988]. The Rastafarians. Boston: Beacon Press. ISBN 978-0-8070-1039-6.

- Bedasse, Monique (2013). “”To Set-Up Jah Kingdom” Joshua Mkhululi, Rastafarian Repatriation, and the Black Radical Network in Tanzania“.

- Campbell, Horace (1988). “Rastafari as Pan Africanism in the Caribbean and Africa“. African Journal of Political Economy, 2(1), 75–88. JSTOR 23500303.

- Cashmore, E. Ellis (1983). Rastaman: The Rastafarian Movement in England (2nd ed.). London: Counterpoint. ISBN 978-0-04-301164-5.

- Chawane, Midas H. (2014). “The Rastafarian Movement in South Africa: A Religion or Way of Life?”. Journal for the Study of Religion, 27(2), 214–237. JSTOR 24799451.

- Chevannes, Barry (1994). Rastafari: Roots and Ideology. Utopianism and Communitarianism Series. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press. ISBN 978-0-8156-0296-5.

- Clarke, Peter B. (1986). Black Paradise: The Rastafarian Movement. New Religious Movements Series. Wellingborough: The Aquarian Press. ISBN 978-0-85030-428-2.

- Edmonds, Ennis B. (2012). Rastafari: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-958452-9.

- Fernández Olmos, Margarite; Paravisini-Gebert, Lizabeth (2011). Creole Religions of the Caribbean: An Introduction from Vodou and Santería to Obeah and Espiritismo (2nd ed.). New York and London: New York University Press. ISBN 978-0-8147-6228-8.

- Francis, Wigmoore (2013). “Towards a Pre-History of Rastafari”. Caribbean Quarterly, 59(2), 51–72. doi:10.1080/00086495.2013.11672483. S2CID 142117564.