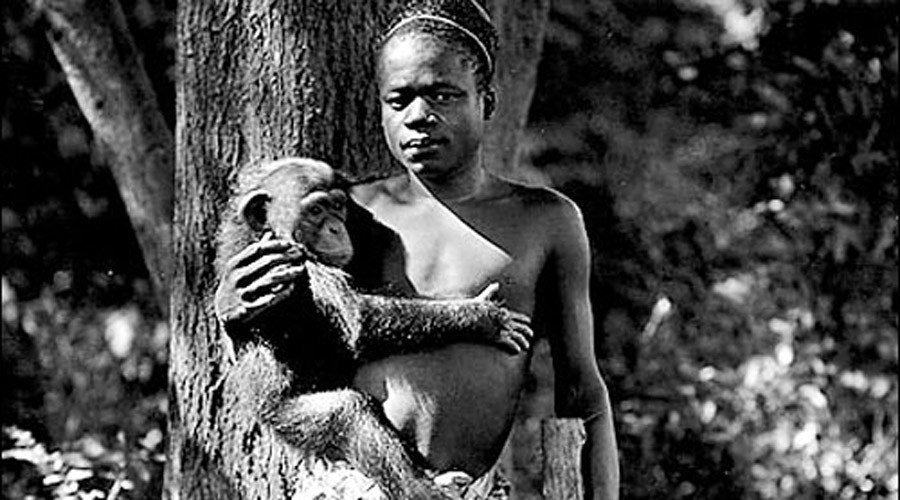

Ota Benga, a young African boy, was kidnapped from Congo and taken to the United States of America. He was put in a zoo with monkeys and displayed them together on arrival.

Ota Benga was a Congolese Mbuti pygmy, best known for being featured in an exhibit in the Bronx Zoo in New York with monkeys. He was brought to America by businessman, missionary and explorer Samuel Phillips Verner to feature in an anthropology exhibit at the Louisiana Purchase Exposition in St. Louis, Missouri, in 1904. He was part of a group of African tribesmen displayed as examples of “earlier stages” of human evolution to demonstrate the then-popular cultural evolution theory. He later got his human zoo exhibit in 1906 at the Bronx Zoo and was subsequently placed in the Monkey House exhibit alongside Dohong, a trained orangutan. Later in his life, he was taken into custody by Reverend James M. Gordon, who arranged for his education and later employment at a tobacco factory. However, after his dreams of returning to his homeland were crashed at the onset of World War I, he committed suicide by shooting himself in the heart on March 20, 1916.

By 1906, he had become popular among the white folk who went to watch him. On September 9 1906, the New York Times published a report about a young African man on display in the monkey house in New York’s largest zoo. The article referred to him as “a so-called “pygmy”, and they used the headline “Bushman Shares a Cage with Bronx Park Apes”. The paper reported that over 500 white folks had gathered that day with their children to laugh and jeer at Benga. Reports say that he was 23 years old but still had a boy’s body.

The outing on September 9 was good for the zookeepers because they had a large turnout. They were expecting the next ones to be bigger, so they moved the boy to a much larger cage, where he was joined by an orangutan named Doing. As the crowd gathered and made jest of him, he sat still and stared at them in wonder. He wonders how people could be so mean as to steal him from his home and treat him like an animal.

By the end of September 1906, over 220,000 people had gone to the zoo to see Benga. In their natural sense and conscience, one would wonder what was so fulfilling in caging and molesting a young boy. But no matter how much one wonders, one would still conclude that white America has no conscience or soul.

The inhumane and vicious display of Ota Benga started spreading worldwide. But as expected, the Caucasian world endorsed it, while many Black ministers, scholars, and persons were angered by the insult of placing a Black man in a cage with animals.

On September 10, 1906, a few Black ministers gathered at Harlem’s Mount Olivet Baptists Church for an emergency meeting about the matter. It was led by Reverend James H Gordon, who was popular then and hailed by the Brooklyn Eagles as “one of the most eloquent Negroes in the country”.

After a few words, he and the other ministers headed for the train station, boarded a train and went to the Bronx Zoo, where Benga was imprisoned with animals. On arrival, they found Benga in the cage with the Orangutan, Doing.

They tried to communicate with him, but he was not in the mood to speak or relate to anyone. He wore a sad face and only stared at them. This made them more furious. They confronted the zookeepers, and Gordon fumed saying that. “We are frank enough to say we do not like this exhibition of one of our races with the monkeys. Our race, we think, is depressed enough without exhibiting one of us with apes. We think we are worthy of being considered human beings, with souls.”

But nothing the ministers said was essential to the zoo authorities. The zoo director and curator, William Temple Hornaday, defended their actions bravely, claiming that it was done on the ground of science.

He said, “I am giving the exhibition purely as an ethnological exhibit,” he said. He stubbornly insisted that their dehumanization of Benga was in keeping with the practice of “human exhibitions” of Africans in Europe, breezily evoking the continent’s indisputable status as the world’s pinnacle of culture and civilization.

The ministers pressed harder with their complaints and displeasure, but Hornaday was unrepentant. He declared that the exhibition would continue until the Zoological society asked him to stop. He knew he had the backing of the Zoological Society and many highly placed government officials, so there was no way they would ask him to stop. At the time, he was a close friend to the President, Theodore Roosevelt.

The ministers failed in freeing young Benga that day, so they left in anger and promised to make a case for Benga at the office of the Mayor of New York. But what they didn’t know was that a significant number of white America did not feel remorse for having a Black boy in a cage. That’s why, when the New York Times personnel heard of what the Ministers did, they were angry and published an inhumane submission – something a media house should not do.

New York Times published the following: “We do not quite understand all the emotion which others are expressing in the matter,” the paper said in an unsigned editorial. “Ota Benga, according to our information, is a typical specimen of his race or tribe, with a brain as developed as its other members.

Whether they are illustrations of arrested development and closer to the anthropoid apes than the other African savages or viewed as the degenerate descendants of ordinary negroes, they are of equal interest to the student of ethnology and can be studied; with profit.”

They stated that it was absurd to imagine Benga’s suffering or humiliation. “Pygmies are very low on the human scale, and the suggestion that Benga should be in a school instead of a cage ignores the high probability that school would be a place of torture to him … The idea that men are all much alike except as they have had or lacked opportunities for getting an education of books is now far out of date.”

By September 16 of the same year, 1906, the zookeepers released Benga from his cage and allowed him to walk around the zoo park. The rangers guarded and kept an eye on him. That day was overwhelming for the young and sad Benga. About 40,000 people were at the park that day, and they all followed Benga wherever he went.

They would circle, poke and make him fall. At one point, when the crowd seemed like they were attacking him, he struck some of the people in the group. Three men battled to hold him down before returning him to the monkey cage.

The zookeeper, Hornaday, in a protest letter, on Monday, September 17 1906, said the following: “I regret to say that Ota Benga has become quite unmanageable,” he said. “He has been so fully exploited in the newspapers and so much in the public eye, we shouldn’t punish him; for should we do so, we would immediately be accused of cruelty, coercion, etc., etc. I am sure you will appreciate this point.”

Hornaday complained that “the boy does quite as he pleases, and it is utterly impossible to control him”. He expressed dismay that Benga threatened to bite the keepers whenever they tried to bring him back to the monkey house. Hornaday’s star attraction was turning into a liability. “I see no way out of the dilemma,” he wrote, “but for him to be taken away.”

The pressure kept mounting about the state of Benga in the zoo. Many reported that the zoo took money to allow people to enter the boy’s cage. So, on September 26, an investigator was sent from the city controller’s office. His reports shed more light on why Benga should be free.

More newspaper publications decried the use of Benga as an animal exhibit. And Benga himself started to fight everyone and anyone who came close to him. He would bite and kick and even once used a knife to threaten the keepers.

With more street protests and newspaper publications speaking against Benga’s situation, the Zoo curator and keeper released him on September 28 1906. He was taken away quietly without any media notice. He was relocated by the minister Gordon to an orphanage in Weeksville, Brooklyn. The orphanage was named Howard Colored Orphan Asylum and was run m the minister himself.

Gordon gave Benga a room to himself, and he had the freedom to do what he pleased. In an interview, Gordon said that “He looks like a rather dwarfed coloured boy of unusual amiability and curiosity… Now our plan is this: We will treat him as a visitor. We have given him a room to himself, where he can smoke if he chooses.” They taught him how to speak English, which he learned as the days passed.

After a few years in the orphanage, Gordon sent Benga to a Theological Seminary and College in Lynchburg, Virginia. The school was an all-Black school that taught Blacks what the white theological schools had refused to teach them.

Benga grew with the community. He would lead the young boys on many occasions into the nearby forest to teach them how to make bows and arrows and hunt. He seemed happy, but he became withdrawn as the weeks went by. He was depressed and was always talking about going home. He would make a big fire and dance around it alone, chanting his native songs and mourning in pain.

On March 19 1916, out of frustration, he left the house, sneaked into a battered grey shed across from his home, and stayed there. Before morning, he took a gun he kept and shot himself in the heart.