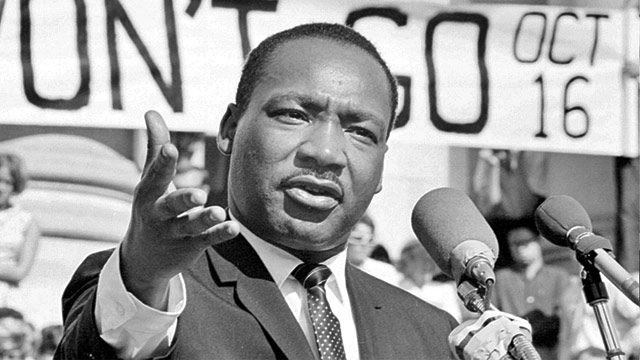

White Americans Aren’t Doing Their Part to finish Racism — and that they Don’t Want to

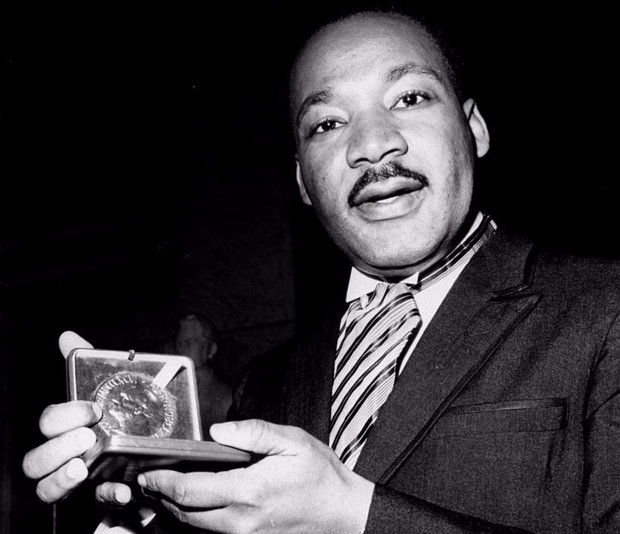

In his final manuscript “Where can we Go From Here?” published in 1967, Luther King Jr., discussed the way white Americans aren’t doing enough to get rid of the stain of racism from America, addressing their refusal to offer up their privilege and learn from the Black people that are oppressed.

“Whites, it must frankly be said, aren’t fixing an identical mass effort to re-educate themselves out of their racial ignorance,” he said. “It is a facet of their sense of superiority that the White race of America believe they need so little to find out. the truth of considerable investment to help Negroes into the 20th century, adjusting to Negro neighbors and genuine school integration, remains a nightmare for only too many white Americans…”

His Thoughts On the risks of Integration

During Dr. King’s last conversation with singer/activist Harry Belafonte at the actor’s home shortly before the reverend’s 1968 assassination, King said he feared he might have done more harm than good with Black people when it involves Integration.

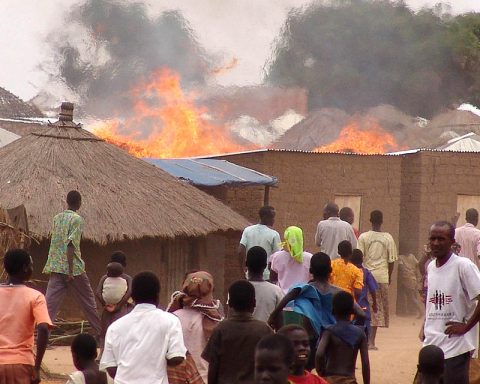

“I’ve encountered something that disturbs me deeply,” he said. “We have fought hard and long for Integration, as I think we should always have, and that I know that we’ll win. But I’ve come to believe we’re integrating into a burning house.

“Until we commit ourselves to make sure that the underclass is given justice and opportunity, we’ll still perpetuate the anger and violence that tears the soul of this nation. I fear I’m integrating my people into a burning house.”

How Some White Americans Don’t Need to Wear Hoods to dam Black Liberation

In 1963’s “Letter From a Birmingham Jail,” King explained the difficulty with a White race who are more concerned with polite demonstrations than doing what it takes to secure Freedom for Black people.

“First, I need to confess that over the past few years, I even have been gravely disappointed with the white moderate,” the activist said. “I have almost reached the regrettable conclusion that the Negro’s significant obstacle in his stride toward freedom isn’t the White Citizen’s Councilor or the Ku Klux Klanner, but the white moderate, who is more dedicated to ‘order’ than to justice; who prefers a negative peace which is that the absence of tension to a positive peace which is that the presence of justice…”

A Man No So Turned Away By Violence

While many of us drop King’s quotes to espouse peace, the icon wasn’t entirely against violence toward the top of his life. After the riots of 1967 rocked the state that summer, King spoke at the American Psychology Association’s annual convention in September, explaining Black people don’t riot for the rationale some might imagine.

“Urban riots are a special sort of violence. they’re not rebellions,” he said. “The rioters aren’t seeking to seize territory or to achieve control of institutions. They’re mainly intended to shock the white community. They’re a distorted sort of social protest. The looting which is their principal feature serves many functions. It enables the foremost enraged and deprived Negro to require hold of commodity with the convenience the man does by using his purse. Often the Negro doesn’t even want what he takes; he wants the experience of taking.”

Taking Back the facility of “Black.”

During a speech reported to possess taken place in Atlanta on Aug. 11, 1967, King discussed the way “black” had been transformed into a negative word, and then it had been used, in turn, to explain African-Americans. He vowed to form the “black” so positive that attendees would pride themselves in their race.

“Somebody told a lie at some point. They couched it in language. They made everything black ugly and evil. Look in your dictionary and see the synonyms for the word black. It’s always something degrading, low, and sinister. Check out the word white; it’s still something pure, high. Well, I wanna get the language right tonight. I wanna get the language so right that everyone here will exclaim, ‘Yes! I’m Black! I’m pleased with it! I’m Black and beautiful!”

King Hit Back At Critics of the Movement

When writer Faulkner said during a March 1956 Life magazine essay that he would caution the NAACP and civil rights activists to “Go slow now. Stop now for a time, a moment,” to offer white southerners time to urge won’t to desegregation, King hit back during a Brooklyn, NY speech later that month.

“We can’t slow up due to our love for democracy and our love for America,” he said. “Someone should tell Faulkner that the overwhelming majority of the people on this globe are colored.”

Power has got to Be Rebalanced Systemically

In his 1967 speech, “The Three Evils of Society,” King explained the importance of rallying support for the Black community to balance power among races — meaning the White race must do their part, too.

“The problems of racial injustice and economic injustice can’t be solved without a radical redistribution of political and economic power,” he said. “We must further recognize that the ghetto may be a residential colony. Black people must develop programs that will aid within the transfer of power and wealth into the hands of residence of the ghetto in order that they’ll, actually, control their destinies. This is often the meaning of the latest Politics. People of will within the larger community must support the Black man during this effort.”

The War In Vietnam may be a Ridiculous Expense Compared to the value of Freedom

In his 1967 speech “Beyond Vietnam: A Time to interrupt Silence,” King discussed the necessity to place an end to the Vietnam War so as for Black liberation to be achieved

“A nation that continues year after year to spend extra money on military defense than on programs of social uplift is approaching spiritual death,” he said.