Feminism is when you fight for the equality of everyone, not just women. But today’s story revolves around how women’s role in the decolonisation process in Nigeria was undermined.

When we talk about equality and opportunity, we talk about cerebral opportunities because men and women are generally physiological different by nature.

While African history is one of the oldest in existence, there have always been women who fought and consistently found ways to oppose the patriarchal society. Feminism has always been an integral part of African women’s history.

In the traditional Igbo society, Sitting on a man includes singing, dancing, and throwing stones in front of the man’s hut. The episode can reach its climax with the destruction of the man’s building. The emphasis here is that cultural facilities existed that provided a stepping-stone to women’s agitation deep-rooted in culture before the advent of the colonialists.

Generally, in African societies, the opinion of if society was patriarchal or not was never in the picture. This is because African women played a complementary role in the society and community they belong to. Just like the Umuada of current day Igbo traditional society, such age-grade systems helped showcase the women’s participation in the society. Therefore the relationship between the males and females in traditional Igbo society was like that of “Bread and Butter.” You can’t do without the order.

With colonisation came a constitution that subconsciously restructured the society into a form of a male-dominated system, different from what was already existing. A critical review of various colonial legislation, namely the 1922 Clifford Constitution, the Sir Bourdilion Constitution of 1939, the Arthur Richards Constitution of 1946, the Macpherson Constitution of 1951, and the Oliver Lyttelton Constitution of 1954—under which colonial rule in Nigeria operated—all point to raising men for leadership and the relegation of women by extension. According to Modupeolu Faseke, these male-dominated constitutions created institutional prejudice (Faseke,1995:2), which persists in Nigeria up to date.

To state that women played critical roles in the decolonisation process in Nigeria may sound odd because we are used to hearing patriarchal figures such as Nnamdi Azikiwe, HerbeHerbert Macaulay, etc., as the fathers of Nigerian nationalism. Historical evidence points to the direction that King Jaja of Opobo, Nana of Itshekiri and Oba Ovaranwen were the pioneer nationalists because of their resistance struggle against British colonial rule. Yet they were not acclaimed fathers of the nationalist movement in Nigeria.

With the vast demographic loss of women’s roles in the decolonisation process and the activities of Magret Ekpo, Janet Mokelu, and Funmilayo Ransom Kuti, there would have been a sense of equity if any of them had been placed as the mother of Nigeria nationalism. But no, the history was written by patriarchally biased individuals.

Here are significant roles played by women in the decolonisation efforts omitted by history;1949 and 1954, respectively.

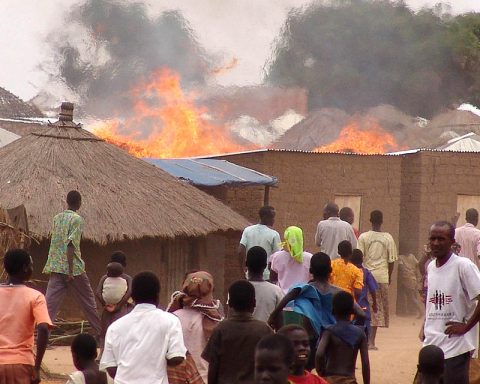

The killing of twenty-two coal miners, mentioned earlier in the paper in Enugu, triggered Janet Mokelu’s demonstration in Enugu and Magret Ekpo’s demonstration in Aba, respectively. These women felt that men were silent over gross injustices; thus, they revolted. In November 1949, a labour protest saw the annihilation of twenty-two coal miners, which warranted a protest led by Magret Ekpo alongside Jaja Nwachukwu, S.O. Mazi, Janet Mokelu, and others. Attoe and Odini account Magret Ekpo frown as follows: “The colonial government should thank their stars that only men were killed, if any women had been killed, I would have made a fire to burn at Aba” (Attoe and Jaja, 1993:23).

Another example of women’s revolt actions was the Dance Revolt of 1925. It was pronounced among women in Akpuje and Owelli towns of Awka. In the Onitsha Province of Ihiala, Nnewi, and Nobi town: in Ohazara, Okigwe, Bende and Umuahia, the Dance movement was envisioned. Women from Owerri province came to Ihiala. From Ihiala, they visited Nnewi, and from Nnewi, they proceeded to Nobi. The women dancers of these towns came together and placed obstructions on one of the main provincial roads. They then proceeded to Nobi court, burnt the market and filled the court with refuse(NAE, M.P No. 18/1926 Memorandum From The District Officer Onitsha To Senior Resident Onitsha Province). The reason for these actions was justified as follows:

English money should do away with entirely and that cowries must come more for use; to pay only one bag of cowries for marrying young girls and a half bag for marrying a woman, and that men must not go to market but women (NAE, M.P No. 18/1926 Memorandum)

In Eastern Nigeria, activities of the Women’s War of 1929 were all responsible for the demise of the Warrant Chief system in Igboland. On record, women took to the streets of Olokoro, Aba, Ngor Okpala, Ibibio, and so many areas of Eastern Nigeria to protect against the obnoxious practices of the Warrant Chiefs appointed by the British colonial administration. Women leaders such as Nwanyeruwa, Ikonnia, Nwanedia, and Nwugo should have occupied eminence as matriarchs of the nationalist struggle against British imperialism. Even in historical scholarship, a book acclaimed to be a compendium of Nigerian history, Ikime (1980) (ed) Groundwork of Nigeria History did not include a chapter highlighting women’s history in Nigeria. This excellent book, used in teaching Nigerian History across universities in Nigeria, ought to include women’s role in nation-building.