“Forgive me, father, for I have sinned,” I said in a profound contrite tone displaying the deep-seated regret that ran through my soul.

“Speak my son” The clear whispering voice of the priest sipped through the numerous holes that separated us both in the confessional “What sins have you committed?”

My hands were clasped together beneath my chest tightly in an undying piety for Christ, my eyes misty from the regrets that tore through my conscience.

What have I done?

Why did I do it?

Did the Catechism not warn me early enough?

Now, I have fallen short of the glory of God.

I have sinned, and the mercy of God must be attained, or my destination is sealed.

I can still vividly remember my sin. It played out freshly in my memory; Kneeling right there before the Priest of Christ, the sacrament of penance, atoning for my abhorrent action.

It was just four days ago we got back from the village. The new school year was about to start, so I had to wrap up my village vacation stay with my Grandmother.

I always relished the idea of spending my vacations in the village, spending time with my grandmothers, both of whom lived in our small village but more especially because Papa was not around to put a check on my behavior. I was free to roam around every day, jumping from one tree to another, howling wildly in the bush chasing after bush rats, grasscutters, and snakes.

Mine was the untamed happiness of a child free from the prying correcting eyes of his Father.

My friends and relatives in the village, boys my age would come to get me as early as 8 am. We would run off for the day. I just had breakfast; enough energy to get me through the morning, wild fruits and nuts from the bushes we ran around in will do for lunch and then we are off to the forest to burn calories chasing after little Bush meats that ran as if they had something to win – they did have something to gain; their lives.

Grandma surely always had dinner waiting.

As Papa came down to the village that weekend to take me back to the city, I was being beaten by my conscience. Every look from Papa felt as if he could read me like a book, I felt vulnerable, as if he could see right through my eyes every picture of the sin I’ve committed just a day before.

Papa would disagree strongly. He would be angry.

“You are a Christian boy” He’d say, “Your Father is strong in the catholic faith. I won’t have any of my children dragged to the scorching fires of hell.”

Wait till he finds out what I had just done. It would be as if the fires of hell lurked around somewhere beneath me. God surely will remove my name from the book of life for this one.

I was silent throughout the journey back to the city.

“Don’t worry son, I will bring you back after the term is over” Papa said with a tone of concern over my mood. He had imagined I was unhappy to end my holiday.

He was wrong.

It was the day before Saturday, Friday. I woke to an air of festivity around the Agbaeze compound. The fires and aroma of food coming from the kitchens of Mama Nnenna and Mma Oyina were too good to be just an ordinary breakfast, which most times were steaming soups warmed from yesterday’s leftovers going down with hard cold fufu that scratched your throat as they slid down.

It seemed there was an occasion everyone was getting ready for. It is not Christmas, neither is it Easter, so, naturally I was confused about what the event was.

Ebuka came down towards my Grandmother’s hut, he was munching over a large chunk of chicken lap, this early morning, steam rose from the meat, peppered juices smeared all over his face.

“What is happening?” I asked, trying to say that in our local dialect.

“Oduigbo is coming home today!” He happily announced, taking a deep bite into the meat.

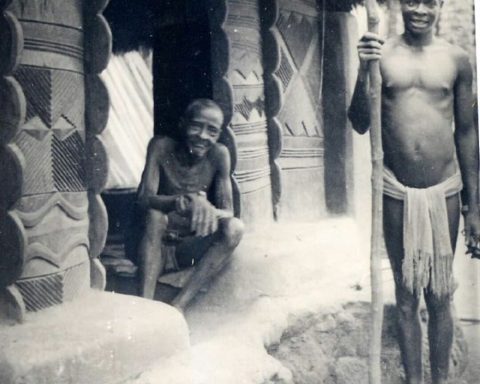

Oduigbo is a masquerade, managed and fixed by our Umunna, our hamlet in Amaowerre Edem of Umulumgbe.

In our town of Umulumgbe, much like most parts of Igbo land, masquerades had a spiritual significance. There were more than masked men chasing and scaring boys and women as the playful ones are. They were revered spirits of the ancestors, wise and just, ancient warriors with brave deeds to their names; So, their coming was expected, celebrated, and comes with a hope of blessings and messages from the land of the ancestors to the adherents of Odinani Igbo.

That was the occasion today.

In our family, my Grandfather was the first Christian; hence his wife and son (Papa) are Christians.

But not everyone in Agbaeze family is a Christian; Nnam Ode wasn’t – a wise man, a physical specimen of the unnatural height that ran in the Agbaeze blood, a good man in every way.

His wives Mama m Oyina and Mama Nnenna, the youngest, are preparing the meals for today’s festivities.

I could see the egusi soup as Mama m Oyina turned it in the pot, there was hardly any water in it, large chunks of meat poking out here and there, I couldn’t help but swallow my spit.

Other delicacies would also be available; Okpa freshly made with new palm oil, roasted yam to go with Ugba, Abacha and Akidi, Agbugbu and achicha. A goat will be killed and devoured right there in the presence of the newly arrived ancestral spirit.

Ebuka had explained it like thus; After the cookings are done, the men will go to the Oduigbo shrine with beer, palm wine and canons to signal the arrival of the much awaited spirit, the women will carry all the delicacies prepared to the shrine where everyone will participate in the rituals, eat all the food, drink the wine and take home the blessings from the land of the ancestors.

The women were gathered, clad in uniformed wrappers, their legs adorned in uhie (Red dyes) down to the sole of their feet.

The men headed for the shrine. There was no way I could miss everything I have just seen and heard, I tagged along, asking more questions as we went.

Grandma didn’t know where I went to, if she had, she would have threatened to tell Papa.

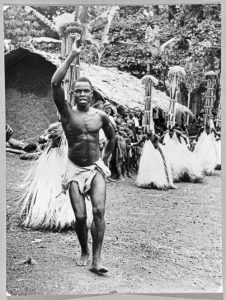

A little after 5 pm, the masquerade arrived, well decorated with new clothing prints, newly painted masks, its large white horns shooting up stupendously, he was a beautiful spirit.

The kolanuts were split and shared, the prayers were said, the rhyming incantations and messages from the masquerade rang out into the air, it bore messages of glad tidings, I thought the tenor voice that sang underneath the clothing decorations were amazing, amplifying echo from the chambered hollow mask.

After the bit, it was time to eat and drink, every food brought to the shrine must be consumed, no one was allowed to deny the other what they wanted to eat. Men were chatting and laughing, beer and palm wine trickling down their chins, and they greedily washed them down, finishing with a roar.

I hesitated. Participating in the consumption of food sacrificed or dedicated to a pagan deity was prohibited for a Christian.

How many times has Papa warned me about avoiding anything pagan?

How many times did I hear that from the catechism teachers?

The bible? God punished the Israelites for such sin.

People asked why I was not eating, I tried to smile it off, working hard to resist the urge to unwind, join everyone else in their happiness and festivities.

Needles to say, I caved in, dove deep to help myself, the Okpa was out of the world, hardly any dip into the soup came without a chunk of meat in my hand, the fufu, freshly made, soft and oozed in all glory.

It was the first day I drank a beer. No soft drinks were anywhere in sight. Nobody stopped me, Nnam Ode looked at me with an eye of admiration – This was what manhood was about.

For a while, I forgot, I was buried in the joy of it all, flanked left, right and center by my kin’s men, eating from wooden plates, occasional solo rhymes coming from the now seated masquerade.

It was peaceful and happy.

But the morning after, all my joy and happiness was replaced with guilt and regret, I had committed a grievous sin before God, I had tainted the temple of the holy spirit and broken the vows of my baptism with unholy food and drinks in an unholy gathering.

That was the story I feared Papa could see beneath my misty eyes.

Now? I can still remember the inside of the church, my penance of 25 decades of the rosary proscribed by the priest with a stern warning not to commit this sin again, a reminder that the holy spirit does not dwell in unholy bodies.

I can picture myself going to this confession again. I would do and say things differently.

“I am not here to ask for forgiveness Father, I have done nothing. I ate a food dedicated to the Gods of my fathers, the Gods, and spirits of my ancestors, and I shared moments of joy and peace with my kin, a fellowship much needed in a world marred by hate. I do not regret this Father, and I am happy I did, I will do it again. The bible always talked about Gods of the Israeli’s forefathers, of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, why should I be ashamed of the Gods of my Fathers? The Gods of Uradogwu, the Gods of Ekweka, and Agbaeze? I do not ask for pardon Father, I have not sinned, I only ate from the same plate my ancestors ate from, and I am proud of it.”

That is how I wished that confession had gone. Now I wish my joy wasn’t tainted by regret and remorse over a sin that isn’t a sin.

I am an African man, an Igbo man, Odinani is part of my identity. I appreciate this part of who I am.