The Tiananmen Square protests of 1989, culminating in the Tiananmen Square Massacre, were a series of demonstrations in and near Tiananmen Square in the People’s Republic of China (PRC) between April 15 and June 4, 1989.

The Tiananmen Square protests of 1989, culminating in the Tiananmen Square Massacre, were a series of demonstrations in and near Tiananmen Square in the People’s Republic of China (PRC) between April 15 and June 4, 1989.

These protests were majorly led and organised by Beijing students and intellectuals. The demonstrations resulted from an increment in the cost of living, which corrupt government officials took advantage of.

Although the economy had impressive growth, university students and few intellectuals opted for political and economic improvement. Also, the citizens experienced significant profitability in addition to the improved economy.

The central government in the mid-1980s welcomed and supported some notable intellectuals to get more active in political activities; however, the student-led protests demanded more individual rights and freedoms. These protests caused extremists in the government to halt what they labelled “bourgeois liberalism.”

In response, Hu Yaobang, the CCP general secretary since 1980, was forced to resign from his office in January 1987. He encouraged democratic reforms during his time. However, the driving force for the ongoing events of the 1989 spring was the death of Hu Yaobang in mid-April.

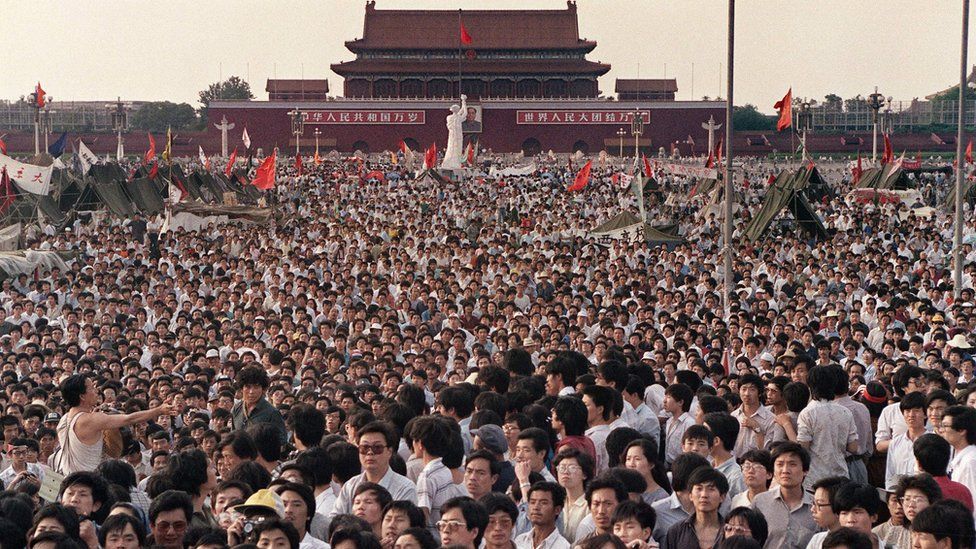

On April 22, over 10,000 students came together in Tiananmen Square, insisting on democratic and other reforms. In death, Hu was made a martyr for the cause of political easiness. Over the coming weeks, students in crowds of varying sizes joined by various individuals seeking political, social, and economic improvement gathered in the square.

At first, the government intended to issue stern warnings and take no action against the gathering crowd in the square. Still, protests and gatherings began to rise daily in various other Chinese cities, notably Shanghai, Nanjing, Xi’an, Changsha and Chengdu.

Nicknamed the “student democracy protest,” the protesting crowd not only wanted democratic reforms but also demanded labour bargaining for workers, a right to a free press and an end to party corruption. This protest was widely broadcast all over the world.

At the same time, there was an ongoing intense debate between the government and party officials on how to contain the increasing protest. Zhao Ziyang, Hu Yaobang’s successor, suggested that the demonstrators be negotiated with and made to understand that their points had been noted. However, they were quickly thrown aside by Chinese premier Li Peng who proposed surpassing the protests cause he feared a case of revolution. He was supported by Deng Xiaoping, who was an elder statesman.

With two weeks left in May, martial law was declared in Beijing, and army troops were positioned around the city. An attempt by the soldiers to get to Tiananmen Square was aborted when Beijing citizens flooded the streets, blocking their way through. However, on the night of June 4, tanks moved into the square and began shooting sporadically. This was followed in other Chinese cities in the coming days. Although there’s no exact death figure, it’s estimated to be between a hundred and 10,000.

The protesters, not relenting, maintained their large numbers in Tiananmen Square, focusing themselves around a plaster statue called “Goddess of Democracy” near the square’s northern end. Western journalists also maintained a presence there, often providing live coverage of the events.

And by the beginning of June, the government was ready to go in again. Tanks and heavily armed soldiers marched towards the Tiananmen Square Shooting and crushed everyone who tried to block their way on the nights of June 3 & 4.

Due to the sympathetic behaviour of the students by the State media reporters, they were removed from their posts. Two news reporters, Xue Fei and Du Xian, who reported this event on June 4 in the daily Xinwen Lianbo broadcast on China Central Television, were laid off because they displayed sad emotions.

The son of former foreign minister Wu Xueqian, Wu Xiaoyong was removed from the English Program Department of Chinese Radio International, apparently for his pity towards the protesters.

Editors and other staff at People’s Daily, including director Qian Liren and Editor-in-Chief Tan Wenrui, were also sacked because of reports in the paper that were pitiable towards the protesters and several editors were arrested.