All through World War II, Nazi officials hunted allied spies and resistance fighters. However, Virginia Hall, who wreaked great havoc by organising sabotage missions and jailbreaks, continually eluded them.

She was born on April 6, 1906, to Barbara Virginia Hammel and Edwin Lee Hall in Baltimore, Maryland. She was born into a wealthy family that ensured she didn’t have a difficult life growing up, and by the time she finished her studies, she was fluent in German, French, Italian and a little Russian.

When asked to define herself, she called herself “capricious and cantankerous.” She had always been interested in being a diplomat with the United States foreign service but was rejected several times because women were rarely hired for the role.

She was employed as a clerk for the U.S. Embassy in Warsaw and, soon after, the U.S. Consulate in Smyrna, Turkey. In 1933 while Virginia Hall was still in Turkey, she and her American friends went on a bird hunting excursion. During this excursion, she had an accident that left her an amputee, as she stumbled while climbing a wire fence and accidentally shot her left leg.

Her left leg was amputated below the knee, and she used a wooden prosthetic for the rest of her life. This accident finalised the fact that her dreams of becoming a diplomat would remain unfulfilled as her leg disqualified her from a job in the foreign service.

She quit her job and moved to Paris in 1940, just before the start of WWII. She became a driver and drove ambulances for the French army, and after the defeat of France in June 1940, she moved to Spain.

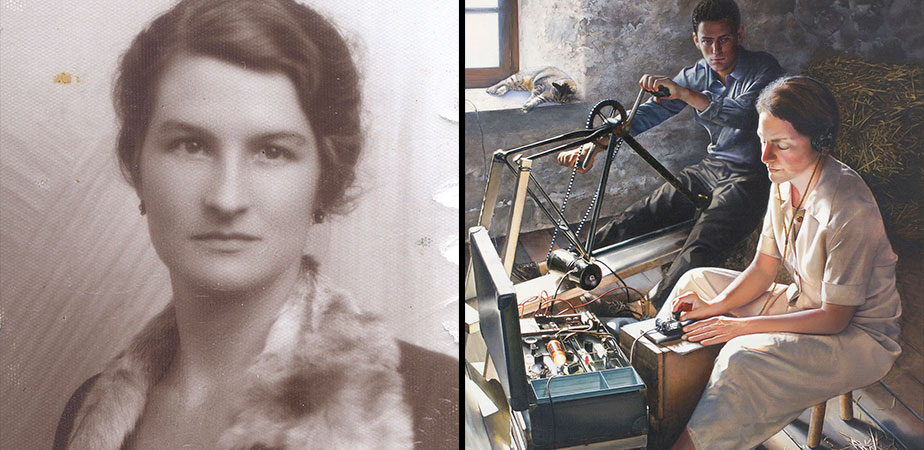

In Spain, she met George Bellows, a British intelligence officer who helped kick start her career as a spy. Her profound knowledge of French country and the fact that she spoke other languages very fluently impressed Vera Atkins, who recruited agents for the Special Operations Executive (SOE), newly created by Winston Churchill.

And in 1941, Virginia became the first female resident agent of the SOE in France. She went in disguised as an American journalist working in New York Post. In this role, she did exceptionally. She also built a network of resistance spies in central France who were very loyal.

During her mission in France, Virginia became so notorious to the Nazi leaders that the infamous Klaus Barbie and the Gestapo put up wanted posters for the “limping lady,” and she was referred to as “the most dangerous of all Allied spies.”

It has been reported that Klaus Barbie, the infamous Gestapo chief, said, “I would give anything to get my hands on that limping Canadian b—-.” However, Virginia was not Canadian, and despite the effort, the Gestapo and Barbie put in, she was never caught.

The Germans nicknamed her Artemis, while the French referred to her as “la dame qui boite”. She aided in helping 12 agents in the custody of the French police escape from jail. This infuriated the Germans, who became more aggressive in dealing with the resistance.

On November 7, 1942, Virginia fled France without informing anyone. She walked for three days in great pain due to her prosthetic. When she got to Spain, she was arrested for illegally crossing the border till the American Embassy got her released.

Despite having a target on her, Virginia was adamant about fighting the Nazis, and in 1944, she disguised as a 60-year-old peasant woman and rode on a British torpedo ship to France. On this mission, her team was said to have blown up four bridges, derailed freight trains, killed 150 Nazis and captured 500 more.

Virginia was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross after the war. This award was one of the highest U.S. military honours for bravery in combat, and she was the only woman to receive the award during World War II.

Virginia Hall died in 1982.