I grew up hearing the word “Ekwensu” used by my Igbo family and friends to represent the Igbo interpretation of the Christian Satan. If someone did something terrible, they would be called a child of Ekwensu, who is bound to go to hell. As children, we were terrified of that name.

Growing up and desiring to know more, I dived into African spirituality and culture, which led me to the study of this being called “Ekwensu”, who has been used to haunt my childhood and threaten me into submission with hellish retributions for my very many sins.

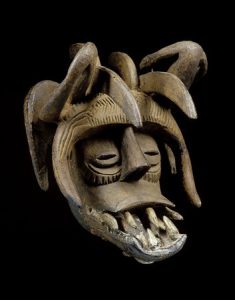

From my research, I discovered, to my greatest surprise, that Ekwensu is not the Satan or Devil of Christianity. Instead, he is a trickster god of the Igbo people who serve as the Alusi (Divine Principle) of bargains. Crafty at trade and negotiations, he is often invoked for guidance in difficult mercantile situations. He is also the deity and force of Chaos and Change; thus, in his more violent aspects, Ekwensu was also revered as a God of War and Victory who ruled over the chaotic forces of nature. He is perceived as a spirit of violence that incites people to perform violent acts. Thus after a war and there is peace, the chaotic aspect of Ekwensu is often banished from the people lest he promotes more wars.

Ekwensu was not originally regarded as the devil. With the rise of Christianity, the more benevolent aspects of the deity were supplanted by missionaries who came to represent Ekwensu as Satan due to a lack of a word that could describe a malevolent concept like Satan in Igbo sensibility.

He was the testing force of Chukwu, and with Ani, the earth goddess, and Igwe, the sky god, make up the three highest Arusi of the ancient Igbo people.

There was never a physical Devil or God in African Spirituality, from ancient Egypt to Nubia to all-around Africa. The fight between Good and Evil is a fight that goes on in our minds. One must strive to become good to conquer the lower self that pushes one to hurt people.

However, one of Christianity’s most wickedly efficient tools in its quest for global propagation was its cultural fluidity. Christianity adopted the practice of translating its fundamental spiritualities into already present and prevalent local spiritualities. In this way, people from these cultures often find it easier to convert to Christianity without feeling that much of their lives have been distorted.

The adoption of Sainthood and their patron roles – directly copied from the ancient practice of recognizing that different divine principalities held control and dominion over distinct aspects of the natural and abstract world.

Adopting existing deities from these local religions and interweaving them seamlessly into the Christian mythos is another culturally appropriative method that made Christian propagation easier.

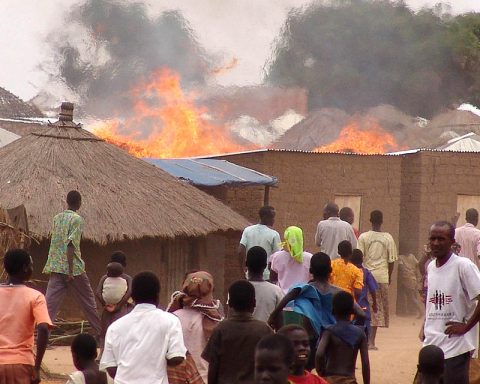

During the advent of Christianity and the colonial enslavement-missionary period, Seth, Èsù, Ekwensu, and many other divine Principles found in different African spiritualities, were transformed to become the Christian Satan, owing to their attributes.

Neither of these deities is Satan or remotely performs Satan’s purely consonant roles in the Christian mythos.

The absence of the Satan force in African spirituality necessitated not the invention but the demonization of a pre-existing deity to fit into that ‘Bad guy’ narrative.

Today, this sinister and unfair distortion of the African culture has been taught to a whole generation of Africans who have grown to hate these ancestral deities and associate them with the Christian mythos of an adverse force.