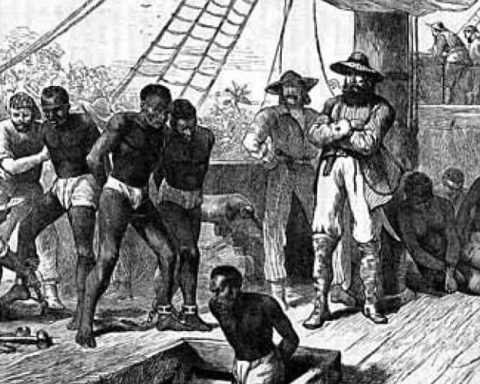

The Georgetown Visitation Preparatory School, an elite girls’ school in Washington, D.C., founded in 1799, has always had an admirable reputation. It was once believed that the founding Catholic nuns allowed enslaved people to attend classes and taught them to read. But recently unearthed evidence contradicts that legend and reveals a different story — the nuns sold as many enslaved people as they could!

In the tumultuous 1820s, Mother Agnes Brent, superior of Georgetown Visitation Convent in Washington DC, was deep in debt. The convent had broken ground on a new church block with stunningly poor timing — a few months after, the country dipped into an economic collapse roused by the Panic of 1819.

To fund the project, Mother Agnes needed money. Quick money.

Then quite unexpectedly, ‘Providence’ came to the rescue; two of the nuns had relatives who offered a “gift” to Georgetown Visitation — their four spare slaves, two adults and two children.

Still, Mother Agnes wanted to know: Did the mother have to come along with the children? And if she did, would the relatives please pay for her costlier room and board until she was sold? She was ready to milk her “gift” through and through.

“If they are so young that they cannot be separated from the mother & the mother be also given, then we would have to request you to get a place for them, free of expense,” Agnes wrote in a letter.

This is just one of the instances documented in a 65-page report compiled by a school archivist and historian and made available online by the school itself. The revelation has destroyed the good image of one of the most prestigious Roman Catholic girls’ educational institutions in the country, plunging the old D.C private high school into a year-long reckoning with a past that was far more entangled with the nation’s slave trade than students and staff had ever suspected.

It was common knowledge that the founding nuns enslaved people, but school lore (aka white lies) has held that the sisters allowed enslaved children to attend Saturday school and defied the law by teaching them how to read. Typical white revisionism. The multi-page report details the businesslike efficiency with which the nuns sold scores of enslaved people to pay off debts and fund new buildings.

The report found that Georgetown Visitation sisters owned at least 107 enslaved people, including men, women and children, from a year after its founding until 1862, when the federal government made slavery illegal in the District.

“It is hard history to read, and that’s the reality of it,” said Caroline Handorf, the communications director for Georgetown Visitation. “But you can’t move forward unless you understand where you’re coming from.”

Handorf said the report, inspired partly by a similar effort at Georgetown University to come to terms with its slaveholding past, has prompted “really powerful and difficult conversations” on campus. After the report’s release, the school held several discussions for students, faculty members, staff and alumnae, and two prayer services honouring the enslaved people. It also incorporated the report into the curriculum of AP U.S. history classes.

Ne’Miya McKnight, a Black 16-year-old rising junior at Georgetown Visitation, said that she was not shocked that her school was built through slave labour. She told white students are even more shocked than nonwhite students.

“Slaves built a lot of D.C. — all over the U.S., but D.C. especially,” McKnight told The Post. “We were glad that Visitation was focusing on this history of having enslaved people on campus — not tapping into that energy, exactly, but just acknowledging it.”

She thinks about the report, which came out when she was a freshman, almost every day at school. It comes to mind when she observes a sea of white faces in class or her eyes fall on old photos of primarily white graduating students.

McKnight’s friends are sometimes upset that “if we lived during that time, instead of being friends with the nuns, we’d be working for them,” she said.

McKnight, though, focuses on feeling proud that her ancestors’ hands built Georgetown Visitation. Like they made the rest of the country.

Susan Nalezyty, a Georgetown University historian who serves as school archivist, said she found no evidence that the sisters at Visitation had ever held classes for their slaves or taught them to read. Nalezyty, who was not available for an interview, wrote that the convent was instead “deeply typical of its time and place,” meaning the nuns bought and sold human beings with impunity.

Previous histories of the school did not include the number of enslaved people the sisters owned or the fact that the nuns made a profit by selling human beings. Deliberate, considering this is a Roman Catholic outfit.

“Georgetown Visitation subsidized its mission by the forced labour and the sale of enslaved people,” the report concludes. “. . . This new research corrects long-held traditions that were not based on facts.

An Indiana University of Pennsylvania professor, Joseph Mannard, who has written about American nuns’ ties to slavery, said many historians of Catholicism would be unsurprised by slaveholding nuns.

He said the earliest convents in America were in the South, and nuns spread across the continent from there. Sisters were steeped in — and broadly accepted — Southern culture, practices and beliefs, including chattel slavery, according to Mannard. What happened at Georgetown Visitation was the norm.

“The nuns were slaveholders in much the same way other slaveholders were, and they didn’t feel guilt, I don’t think,” Mannard said. “I’m not even sure they thought a lot about it.”

According to Nalezyty’s research, Georgetown Visitation nuns thought about their slaves when they feared for the convent’s bottom line. Though the nuns occasionally took steps to keep families together, the documents reveal a scant concern for the human beings whose sales often kept the convent afloat.

Between 1819 and 1827, four new convent and school buildings sprung up in what the report calls an “extraordinary” expansion unprecedented in Visitation history — and over two dozen enslaved people were sold to fund them. While remaining on campus, enslaved people lived “next to the chicken coop and stables,” according to the report; today, the site is a parking lot.

The nuns manoeuvred fiercely to receive full payment for every enslaved person they sold. At one point, the sisters filed at least six separate lawsuits at the same time in a bid to obtain dirty fees!

The Visitation’s story is just one of the countless expositions contradicting regular whitewashed accounts and yet another proof that the white roman Catholic Church was fully involved in the forced subjugation of the Black people, and not just in the brainwashing and spiritual evisceration department.