The Beothuk people have never had a significant population; in fact, they were estimated to be around 800-1000, all of whom are dead.

Their contact with John Cabot in 1497 started the eventual extinction that was to follow for the next 350 years.

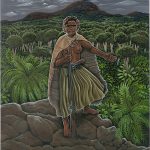

These indigenous people of Newfoundland island were a hunter-gatherer nation. They lived and hunted in family groups, staying inland most of the time and only moving to camp near the river to fish and get water in summer and early fall.

During the camping period, they held festivities, arranged marriages, and traded and exchanged information. Despite being Hunters, they managed their resources efficiently, making sure not to overfish or overhunt any animal.

The first set of Europeans to set their gaze on the sea didn’t build homes and only had camps they stayed in. This made it easier for the Beothuk people to coexist with them.

They bartered silently with these Europeans, dropping things of interest at specific points for them and benefiting from the things they got in return. However, they refused to have anything to do with the firearms left for them.

In the 17 century, this peaceful existence and cooperation came to an end when Europeans began to settle on the coasts, which was the traditional gathering place of the Beothuk people. These settlers also cut them off from the sea, which served as their primary food and drinks water source.

Hunting the Beothuk people soon became a fun activity among the island whites, and they made use of numerous means to hunt them down, and until recently, Alexander bay was known as the bloody bay because it flowed with the blood of the indigenous people.

The whites hunted these indigenous people down because they considered them nuisances in the land they sought to establish for themselves. Eventually, hunting them down became a thing of fun. A common saying among the anglers was that they would rather hunt the Beothuks than fishes.

For more than a hundred years, the murder of a Beothuk wasn’t considered a crime, and when it was eventually considered a crime, none of the perpetrators was ever punished.

For more than two centuries, the Beothucks were hunted everywhere as the settlers competed to see who could kill the most Beothuks.

When the archives of the first Earl of Liverpool went on sale, “the Liverpool manuscript,” which contained long, first-hand accounts of the Beothuk hunters’ adventures, came to light, proving that these stories which were compiled in 1792 and told by word of mouth were in no way exaggerated.

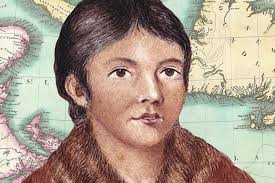

As a result of how unsafe it was to stay in a specific location, the Beothuks kept moving, and many were lost to the cold weather, diseases and hunger that ravaged them. The rest were captured when seen and sold into slavery.

In 1819, the Beothuks that remained were about a handful. In the same year, some settlers captured a woman called Demasduit and her husband, Nonosabasut, was shot and killed when he tried to defend her. His brother was not spared. Demasduit was taken away from her newborn child, who died two days later. A few months later, Demasduit died of tuberculosis. In 1829, ten years later, the last known surviving Beothuk and Demasduit’s niece died of tuberculosis.