The tales of colonial resistance are packed with stories of men who led bravely. We read of leaders like Jaja of opobo, Jomo Kenyatta and the few tales of women like Moremi who fought for the freedom of her people are just being told.

This four series article was written to highlight men and women who fought and resisted colonial rule in their countries.

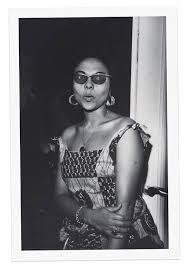

The third part of this series is dedicated to telling the story of Andree Blouin. Popularly known as the woman behind Lumumba, very little has been told about her story.

Born to 14-year-old Josephine Wouassimba and 40-year-old Pierre Gerbillat, a French man, on December 16 1921, in Bessou in Ubangi-Shari (the Central African Republic).

She was taken from her mother to an orphanage in Brazzaville when she was three. In her teenage, she escaped the orphanage and the likelihood of getting married early.

Disturbed by the discriminatory and humiliating experiences of the colonial system, she delved deep into politics.

She became involved with Rassemblement Démocratique Africain (RDA)

The first French-speaking pan-African organisation, in French Guinea, in 1958, just before the referendum, to decide whether to attain independence or remain a colony.

When travelling with her husband, a mine worker, she met Sékou Touré, leader of the independence movement in the French-ruled country. She threw in her weight by organising rallies and giving lectures on independence.

She also lobbied for and counselled many other African leaders, including Ghana’s Kwame Nkrumah, fighting against colonialism. Her work led her to Belgian Congo, where the leader of one of its largest political parties, Parti Solidaire Africain (PSA), recruited her. She became the head of the women’s wing, preaching feminism that caught the attention of everyone.

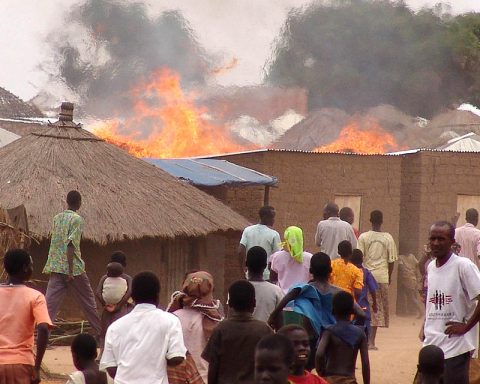

The party later merged with Lumumba’s Movement Nationale Congolaise (MNC) and won its independence in June 1960, although a lot of lives were lost in this battle. Lumumba declared in 1960 that universal voting rights should include women, but they were only granted suffrage in 1967. Blouin became chief of protocol in Lumumba’s government.

Just before Lumumba was executed, Blouin was expelled from Congo. On her way to the airport, she had hidden a political document that had the signatures of Congo’s nationalist leaders. The document also revealed Belgium’s interference in Congo’s transition to independence.

A journalist once asked her whether she was a Communist. She responded, “Let small fools call me what they like. I am an African nationalist.”

In 1973, her husband divorced her, and she moved back to Paris. She opened her home to revolutionaries, catering to them.